On Wonder wall

Naomi Riddle

1.

If you think of steel, you might think of strength. Or you might think of a kind of immutability: cold, astringent, unflinching. You might consider its properties—iron and carbon—and how its base metal must be pulled from the earth, so you might also think of depth, of darkness, of tunnels underground. But metals like steel, or aluminium, or bronze, are well-versed in hiding their true character: that what makes them most appealing is not their strength but their softness and fallibility. They’re malleable, flexible and endlessly adaptable. They acquiesce to being melted, poured, contorted, twisted, rolled and stamped.

Think vulnerable. Think liquid. Think light.

2.

It’s the versatility of materials like steel and aluminium, and, to a lesser extent, bronze, that makes them so ubiquitous in industrial manufacturing. As soon as you look for them, you’ll find them everywhere: in sinks, bench tops, refrigerators, washing machines, car wheels, gutters, beams and frying pans. And yet coaxing these metals to disassemble and rearrange themselves is careful, labour-intensive work. A steel fabricator, for instance, needs to be able to cut, bend and weld the material into pre-defined shapes. The forms need to be replicable at scale, part of a production line of identical components. Fabrication workshops, then, prize efficiency, safety, and speed: How fast can the metal be transformed? What is the most logical and systematic approach?

3.

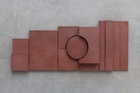

Augusta Vinall Richardson works in the industrial space of the workshop. But she is not seeking to make utilitarian forms or embrace the commercially appealing properties of steel. Instead, Augusta’s process revels in a kind of stealthy slowing-of-the-line. She works intuitively and repetitively; she takes more time rather than less; she overworks the material, challenging its use-value, prizing its tactility, its closeness.

Think circle, rather than arrow. Think loop, rather than conveyor belt.

4.

It starts with a pencil. Working with thick kraft paper, Augusta might draw geometric blocks in stacks, or she might form a constellation of interlocking shapes. There might be gaps or fissures or little windows between the abstract forms. She builds on the surface of the page, redrawing multiple lines and tracing over the shapes. But for Augusta to play with volume and scale—to accrue more layers, more texture, more surface—she must translate these assemblages into three-dimensional forms. She might turn to cardboard (with its fluted, corrugated fibres) and paper mâché, so as to form maquettes, which might then be cast in aluminium and bronze. Or she might use steel sheets, cutting, bending, and welding them into block components.

To move from paper to steel, or from cardboard to bronze, requires the workshop and the foundry. It requires power tools, protective equipment, bulky clothes and physical strength. Just as an outline of the forms begins to appear, Augusta now has a vacant surface to colour, fill and define. The pencil might be swapped for the flapper disc on a grinder. She can glass-bead blast the metal to give it a matte sheen, she can smooth and soften the edges, or she can scratch into a gleaming reflection with a drill bit. In the foundry, once her moulds are set, she can introduce natural chemicals, encouraging a bronze patina.

Augusta speaks to the material and the material speaks back: it exposes its imperfections, or it reveals its specific colour and tone, its aliveness, its ability to converse with, and react to, the properties of the air.

5.

Anne Truitt: “…the fact that I have to use my whole body in making my work seems to disperse my intensity in a way that suits me.”[i]

As much as Augusta is acting on the materials, she is also letting the materials—and the space of the workshop—act upon her. Another way of putting it: she is thinking and apprehending through the body. She must navigate cumbersome and idiosyncratic tools; her body must be adaptive, learn to wrangle machinery and the distinctive properties of metal. In The Writing Life, Annie Dillard says that in France “…when an apprentice [gets] hurt, or when he [gets] tired, the experienced workers [say], ‘It is the trade entering the body.’ The art must enter the body, too.”[ii]

By learning to work in tandem with her materials, Augusta builds up a new sense-memory, a bodily archive of experience that fosters neural pathways, cells and muscle mass. A collision, a merging, between metal and body starts to occur. It’s an intimate encounter that, on the one hand, appears bruising, antagonistic and violent (the metal must submit to being cut or moulded into its new shape, after all), but on the other, it involves great warmth, softness and devotion (the repetitive motions of polishing, smoothing and treating).

Camille Henrot: “Creation of this sort is an ongoing combination of love and aggression.”[iii]

6.

But what of these shapes, these groupings of bodies that lean against, or hold onto, one another? Each of Augusta’s assemblages are modular and non-hierarchal—they’re a collection of forms that are defined not by sameness or sleek uniformity, but by how each distinctive shape complements, and balances, the larger whole. Far from being fused and bonded together, there are absences, blank spaces, small breaths between each shape.

It’s a community, then, that’s precarious and fragile, tender and open. In this way, you could think of Augusta’s sculptures as abstract sketches for more communal ways of being, ones that can slip amongst and underneath the prohibitive structures already around us. When each component’s stability relies on its proximity to others, power relations—and notions of responsibility and care—can begin to loosen and shift and move.

“The goal is to overcome the formative and dependent stages of life to emerge, separate, and individuate,” says Judith Butler, in a New Yorker interview in 2020, “and then you become this self-standing individual. But who actually stands on their own? We are all, if we stand, supported by any number of things.”[iv]

Think vulnerable. Think liquid. Think light.

Naomi Riddle is a writer and editor living on Gadigal land. From 2017-2023, she was the founding editor of Running Dog, an online arts publication that produced regular reviews and long-form articles on contemporary art. Her writing has appeared in Guernica Magazine, Sydney Review of Books, Southerly, JASAL, Memo Review, among others, and she is a regular contributor to ArtReview.

[i] Anne Truitt, Daybook (1982), (New York: Penguin Books, 1984), p. 43.

[ii] Annie Dillard, The Writing Life (1989), (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013), p. 69.

[iii] Camille Henrot, in Ido Nahari, ‘Can Sculpture Be Domesticated? Camille Henrot on Power and Play’, Artnet, (February 20, 2025),

[iv] Judith Butler, in Masha Gessen, ‘Judith Butler wants to reshape our rage’, The New Yorker, (February 9, 2020),