Primavera: The Belinda Jackson Exhibition of Young Artists [Inaugural]

By Linda Michael, published: 01/09/1992

The combination of a circle, square and a connecting/dividing passage take on different configurations in Gail Hastings’ [sculptuations*]: the circle and square may connote rooms in a floor plan, objects in a room, or props on a stage; the passage may refer to a connecting room in a plan, an actual passageway, or a text through which one figuratively travels. On another level, the circle and the square stand in for any number of oppositions, whose shifting relationships are negotiated through our experience of this work, such as subject and object, time and space, signifier and signified. The idea of the passage signals the artist’s attempt to locate a truth or a place between such oppositions. Her work may be characterised in terms of movement, transference, the passage between the arts (drawing, sculpture, theatre, writing), the actors (viewer, artist, object) and between dimensions (two, three and four dimensional). The divide between subject and object is infringed by the union of the viewer and the scene; the divide between time and space by the temporality manifested in the experience of space, the passing of time in a space of passage.

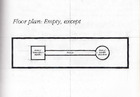

One of the themes of the installation is the simultaneity of, and misregistration between, different kinds of perspectives and points of view; textual, visual and experiential. For example Floor plan: Empty, except appears as both a floor plan and a room. The rooms as registered on the plan are translated into open or lidded boxes situated within a passageway. These objects do not correspond to the plan in a way that we would expect from the codes of architectural drawing. Rather than becoming actual rooms, they materialise as minimal forms deflated to the scale of furniture. The spectator’s point of view shifts a register from that of a controlling perspective over a plan to an encounter with actual objects in a room.

This room is paradoxically also a passageway, on the plan designated as that between a Room of Remembered Mistakes and a Room of Mistakes About to be. As a passageway it may be experienced merely as a place of transit. Lying between the past and the future, and between what is behind and what is ahead, the passage signifies the always changing, ever elusive present. But this elusive space is subject to precise measurement by the artist. The passage and the objects within it are measured, not in metrical units, but in ‘inconsequences, thoughts and conversations’ according to an idiosyncratic lexicon (12 inconsequences = 1 thought, 3 thoughts = 1 conversation), destabilising the unquestioned authority of mathematical equivalents to our apprehension of distance and time (that has its highs and lows, clarities and confusions). Hastings’ art attempts to make an opening for a less constrained, even poetic conception of phenomenological experience and interpretation within extremely strict formal delimitations.

The theatricality of Hastings’ work has its roots in Minimalist sculpture as characterised in negative terms by Michael Fried in his noted essay ‘Art and Objecthood’. However, unlike minimal abstraction or other modernist practices that have sought to empty the work of narrative or symbolic content, Hastings’ interest lies in the fraught, messy passage between the concept (plan) and actualisation of the work. There is evidence of such a troubled transition in the discarded plans that spill from the central box in Floor plan: Empty, except.

The second part of the installation, measuring subjectivity, comprises a series of elements which are both visually and textually inscribed. These include a room and a stage, chairs or props, a story or a script. The layout of the room is again accompanied by a plan. On this occasion the plan is drawn on the ceiling, and again offers a disjunction between our physical experience and our interpretation of the space. The installation plays with different levels of what we might construe as real (including for example the cityscape outside, that is drawn into the installation visually and through the workings of the story).

measuring subjectivity exhibits the distance/proximity between two entitles (for example, two people), and tests the boundaries between the ‘real’ and the fictional. It asks, in Hastings’ words: ‘what happens when someone becomes a character in someone else’s story while they are at the same time themselves?’ The spaces between objects are again measured — this time on the plan, in ‘lost measurements’, suggesting (hoping for?) a collapse of spatial and temporal distance, in the acting out of the (impossible) present.

[* note: This was written prior to the term 'sculptural situation' being coined in 1997. For want of a better word, writers prior to that used 'installation' to describe the work. GH 03.2008]