Exchange between Dr Paula Dredge and Jude Rae:

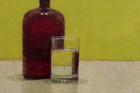

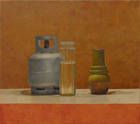

Jude Rae’s paintings of gas bottles, fire hydrants, hardy plants, plastic paint buckets and ceramics demonstrate that oil paint, when skilfully rendered, is incredibly good at representing the texture, colour, the shape of things and the space that they occupy and the light that they reflect. The irony is of course that paint is made of matter. It is just coloured pigment mixed with linseed oil, a miracle of invention and experimentation over 600 years old and enduring.

These works have a bold palette including Mars colours, named for their acidic and unnatural earthiness. As synthetic iron oxide pigments they have a super-charged intensity beyond their chemical analogues of natural ochres dug from the ground. While we know the colour of earth comes in infinite variety, rarely do we see it in such intense hues from yellow and oranges through to purple and black.

However, Rae’s paintings present a puzzle. At first, they are an arrangement of curious things on a bench. We make sense of reverse reflections in water-filled glass containers and on highly-glazed ceramic jars in which we see the artist’s studio window. All seems solid and secure and yet closer inspection suggests our initial perception has deceived us. The orange highlights are in fact the coloured ground layer left unfinished and exposed. The front edge of the bench, seemingly thick and protruding, is physically the most recessed underlayer of the painting. Scale too is strangely oversized, just slightly, but enough to distort our comfort. The raw linen edges and the drips of paint more explicitly demonstrate the seduction of oil paint and its ability to represent and reassure and then to remind us of itself.

Oddly, the discordance also induces pleasure. We recognise the arrangement of objects and the strange ways in which materials and light interact in our world and that perception is more than seeing. More slowly we connect with a deep affection and innate knowledge that we hold for the things depicted, for water, plants and air that are so essential to our lives as earthlings, and for the vessels we make to contain these things.

PD

–

My brief work experience as a teenager in the Materials Conservation lab at the Australian Museum in the early 1970s gave me little more than a glimpse of your discipline Paula but perhaps it laid the groundwork for my interest much later in the puzzle you describe.

As both image and object, a painting is indeed two very different and in a sense contradictory things at once. I love the idea of oil paint reassuring us into a comfortable acceptance of its invisibility then reminding us of its presence. On the one hand a representational painting functions as an image and relies on recognition. Sometimes the smallest reminder of an evanescent moment of vision will carry the work: the way light falls on an object, the sense of form and space this generates …

On the other hand, any painting exists as an object in its own right: coloured mud applied in layers to a support or surface of some kind. I’ve always felt it is a kind of miracle that a few smears of pigment can convey something remarkably subtle about what one person has seen to another person who hasn’t.

There is a balance to be found here between painting as image and painting as object and, like most things human, it plays out across a wide range of cultures and characters in divergent and significantly different ways. I feel, certainly in my work, that either extreme suffocates the experiential dimension of the representation: too much information and detail kills anything that I as viewer or painter can bring to the experience and yet an over-statement of the object nature of the painting — its materiality — somehow impedes the dreaming.

There is something very satisfying in trying to find some — any — kind of balance between image and materiality, form and content, and when it works it is excellent — as good as any sport for both the painter and the beholder.

JR

—

Dr Paula Dredge is teaching the next generation of conservators at the Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation, University of Melbourne, after a long career as painting conservator at the Art Gallery of NSW. She is the author of Sidney Nolan, The Artists Materials 2020, Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles and has a long-standing interest in technical art history.