Oscar Perry: MOON WALKS ON MAN

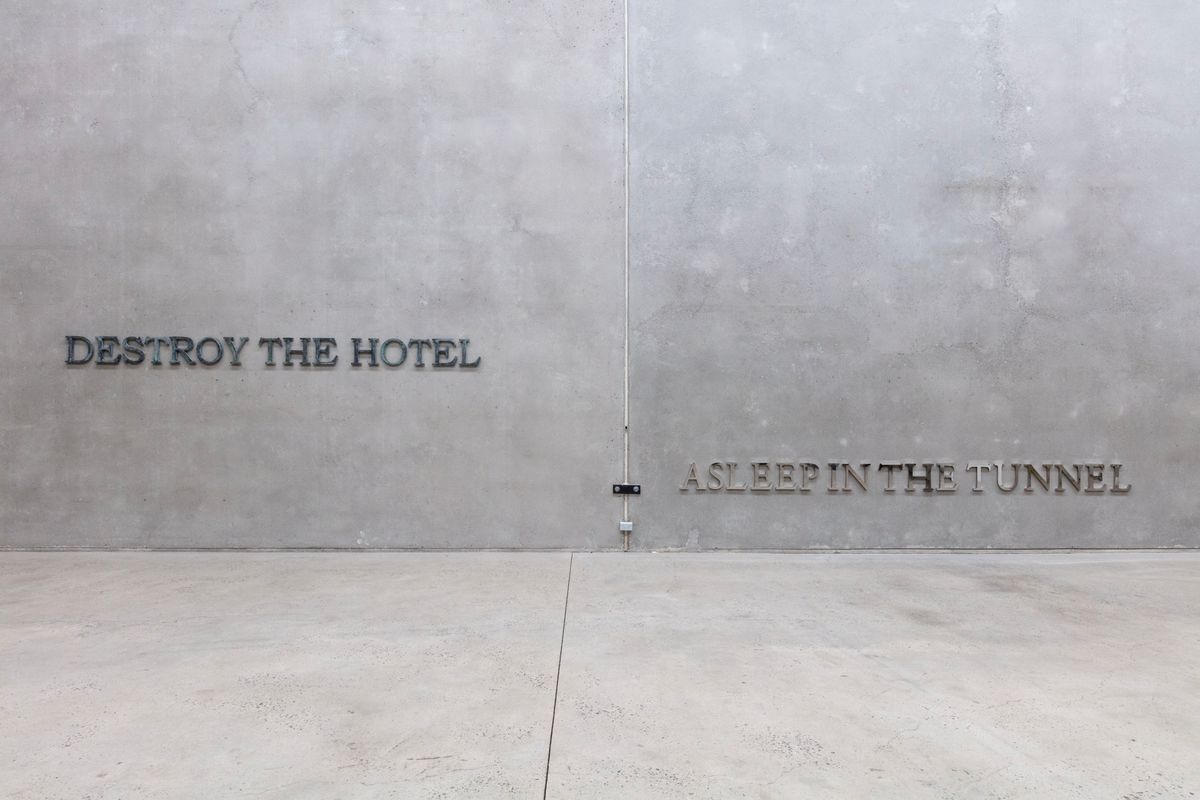

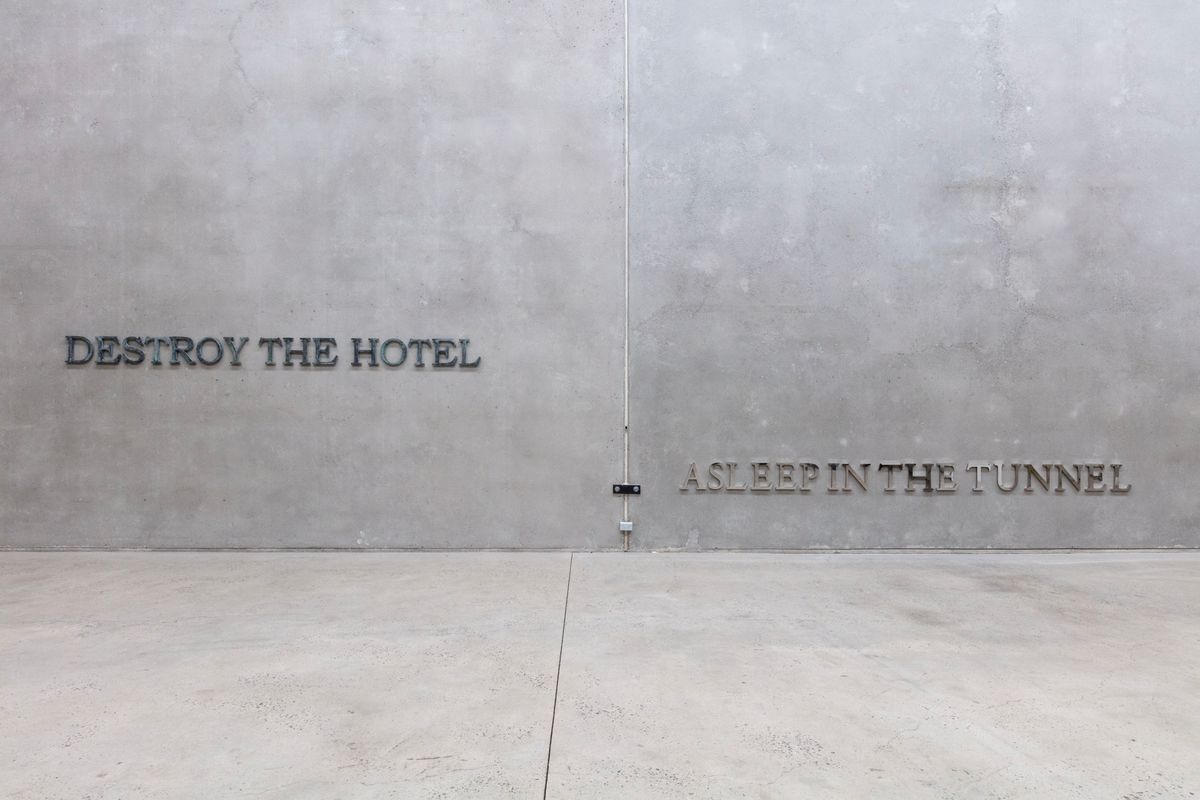

installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney Oscar Perry, Satellite communication system, 2023 - detail Oscar Perry, Satellite communication system, 2023 - detail Oscar Perry, Satellite communication system, 2023 - detail Oscar Perry, Satellite communication system, 2023 - detail installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney installation view: Oscar Perry — MOON WALKS ON MAN, 2023 | at The Commercial, Sydney