Amanda Williams: On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum

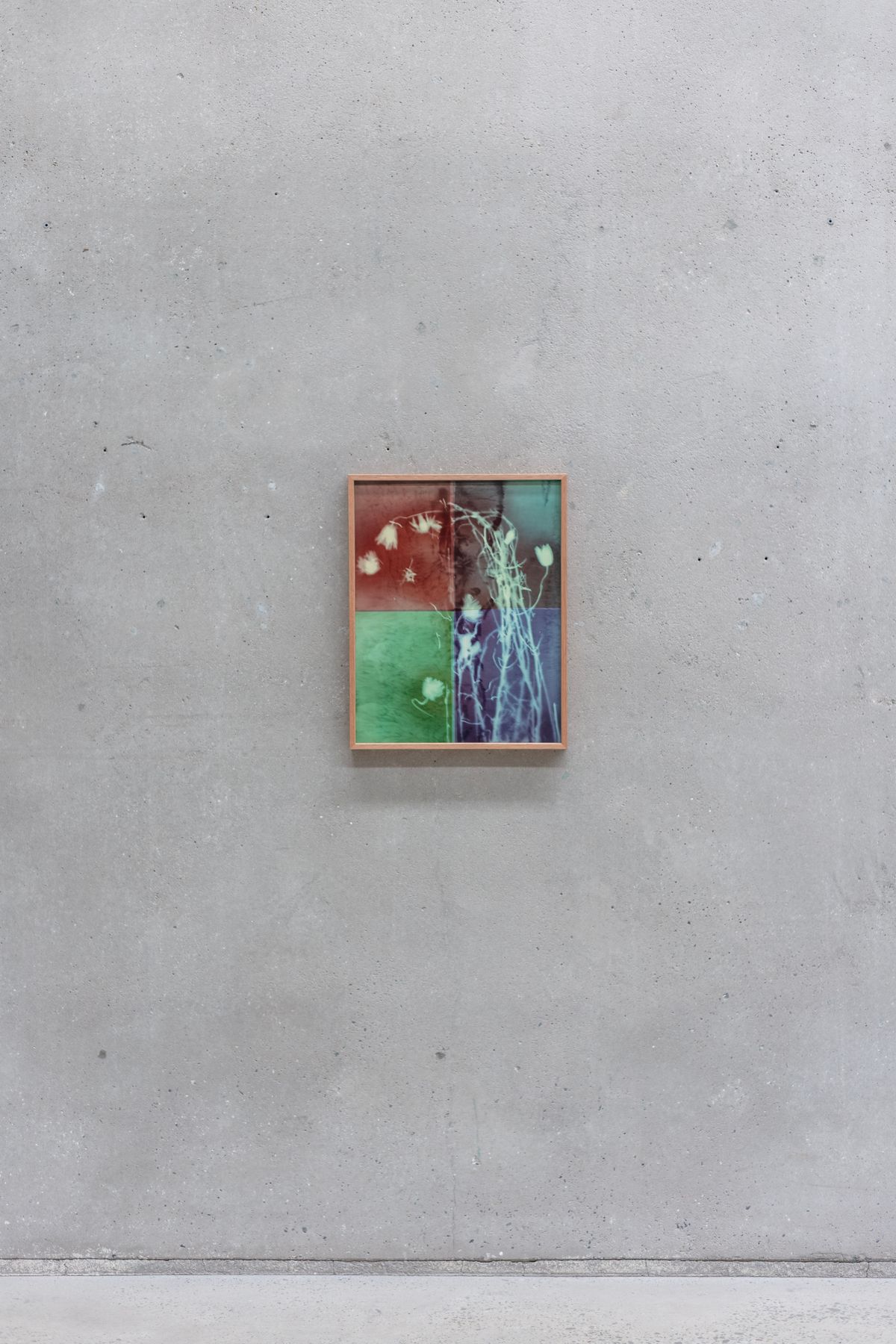

It is with great pleasure that The Commercial presents On the Action of the Rays of the Solar Spectrum, a solo exhibition of new work by Amanda Williams.

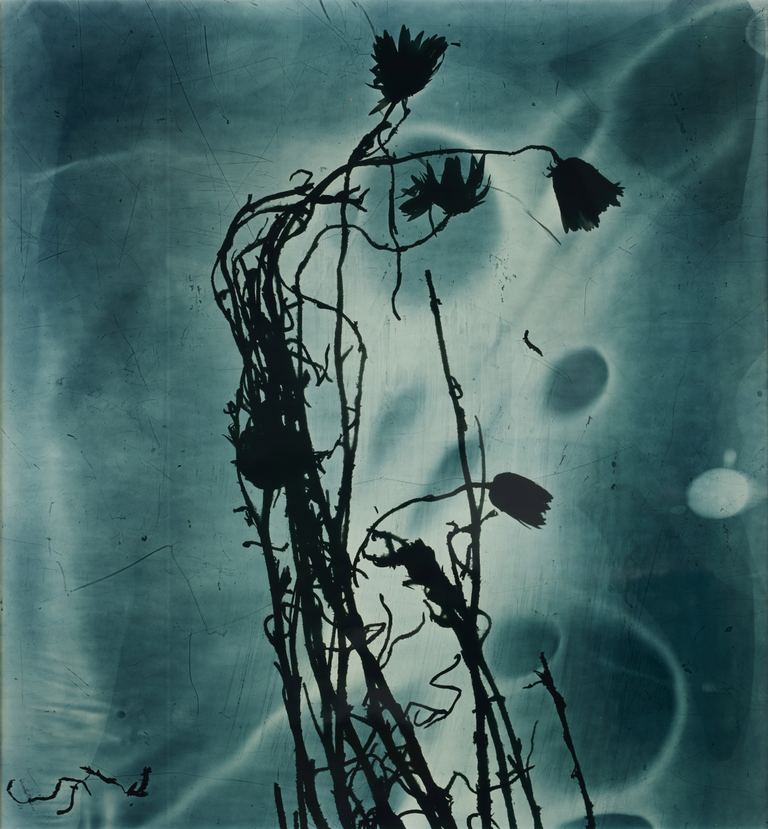

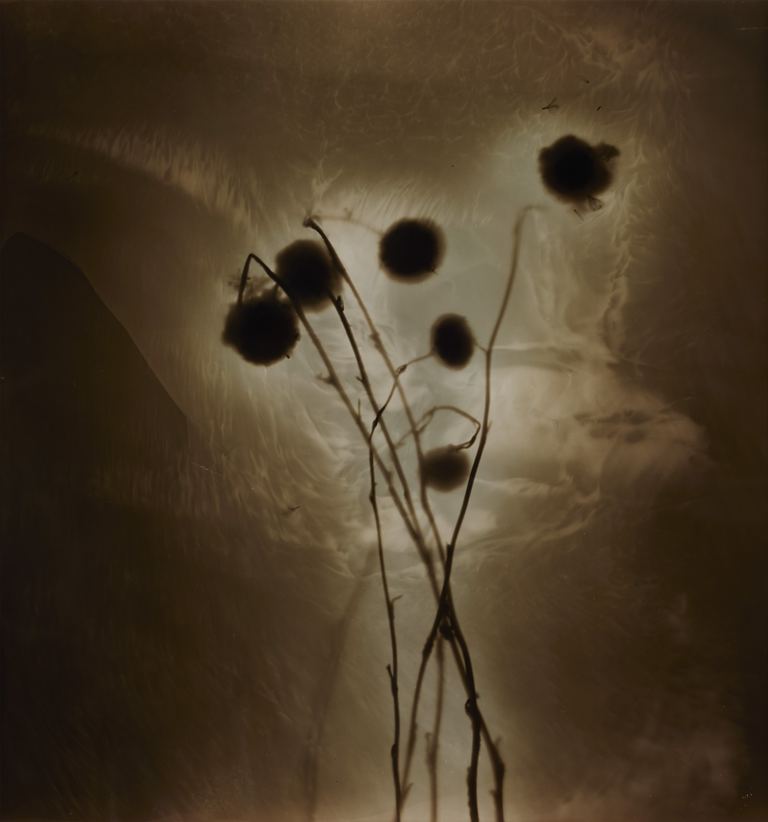

The six chromogenic photographs in the exhibition are a development of Williams’ phytogram transparencies exhibited earlier this year in The National: Australian Art Now at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. Phytograms, made without camera or darkroom, are the outcome of the interaction between the chemistry of plants and silver. The process was outlined by John F.W. Herschel in a paper in 1842 from which the title of Williams’ exhibition is borrowed. While produced via contemporary methods, the colours represented in Williams’ photographs — yellow, rose, sky blue, brown — were identified by Henry Talbot in 1839 as potential outcomes of the surface oxidisation of silver, the basis of black and white photography. Following her earlier landscapes from the same locations, Williams’ phytograms are impressions of flora from Australian Alpine regions.

Artist