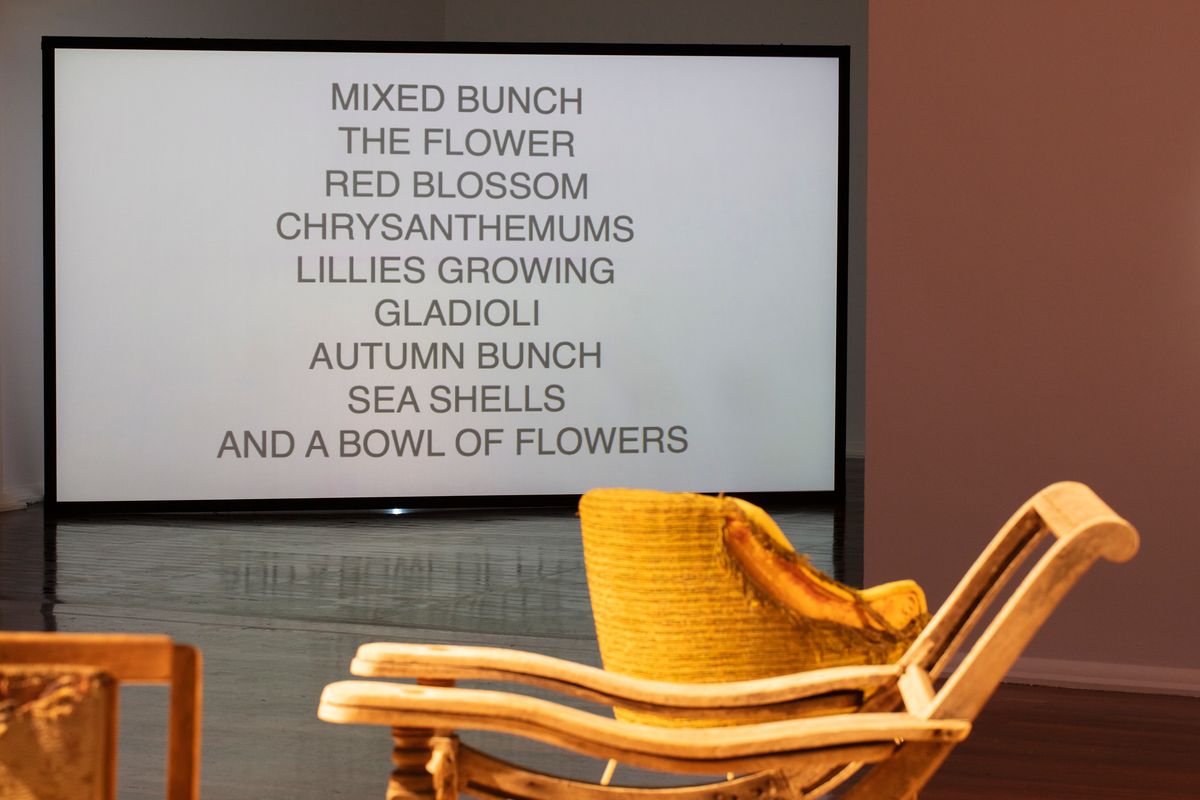

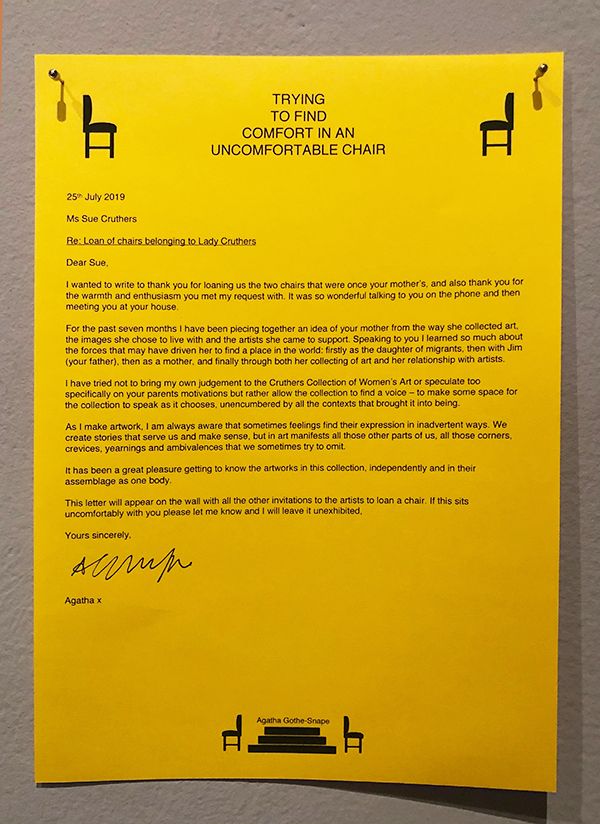

Agatha Gothe-Snape: Trying to find comfort in an uncomfortable chair

If a collection could dream

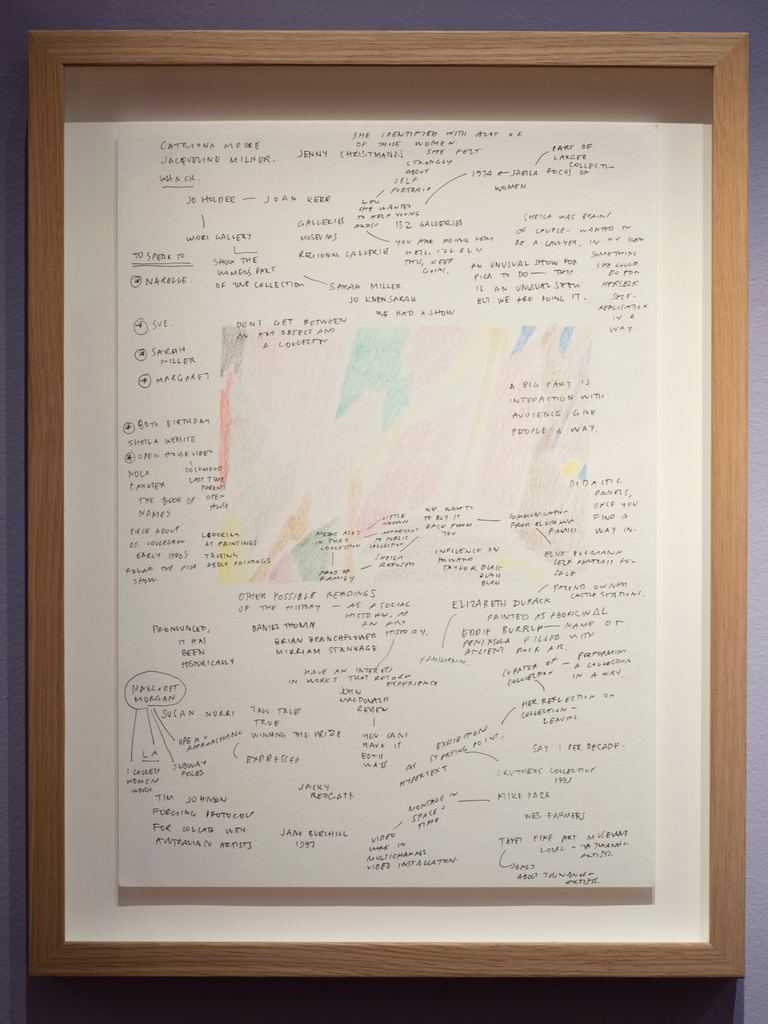

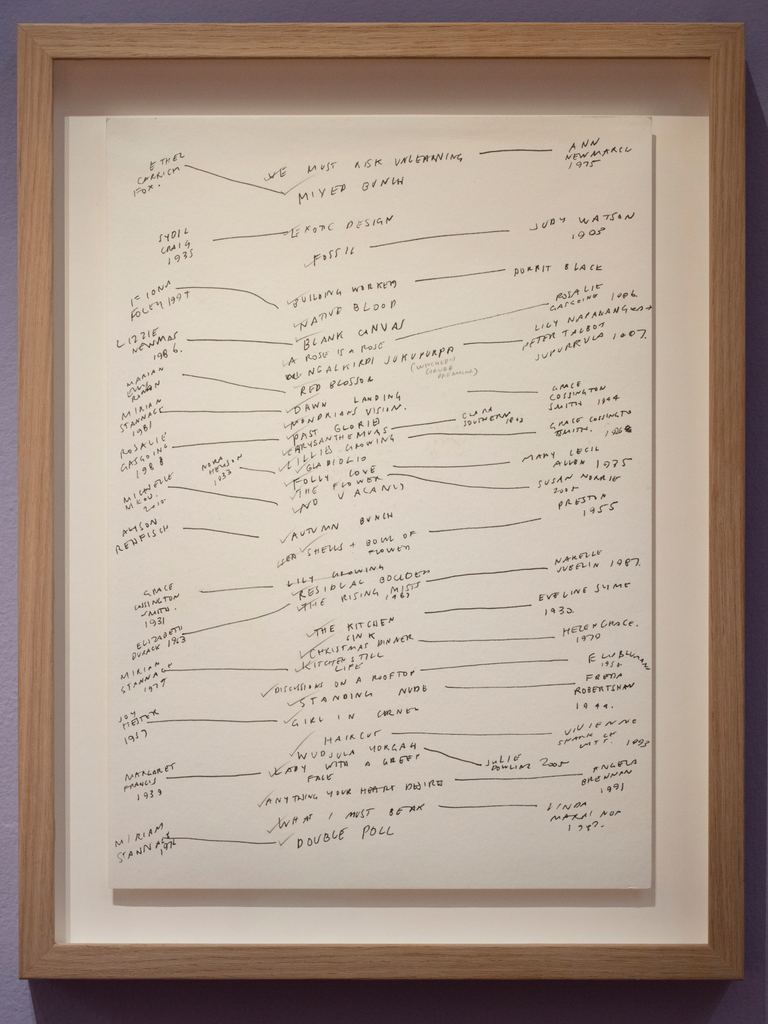

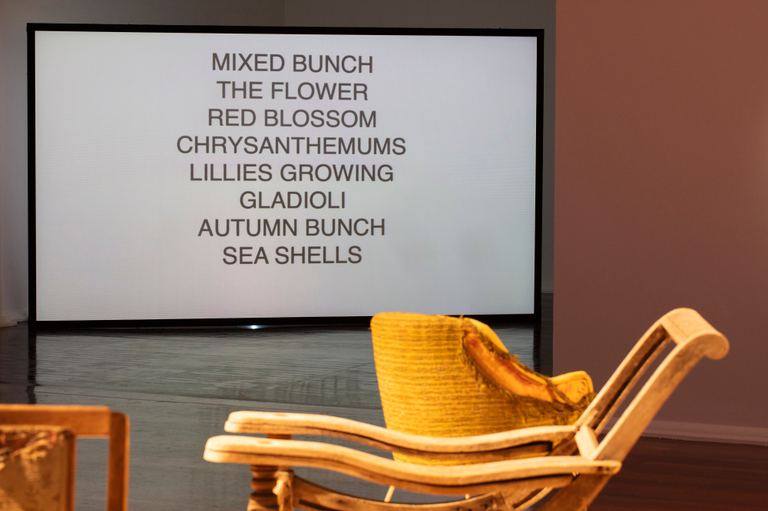

In December 2018, Agatha Gothe-Snape spent a week at The University of Western Australia’s Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery immersing herself in the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art. Agatha is in another sense already immersed in this collection, which includes her installation Certain Situations/EXPRESSION CURTAIN, 2013; the large-scale performance document and drawing Every Artist Remembered with Elizabeth Pulie, 2009; and a subscription to her ongoing series of PowerPoint animations begun in 2008 and updated at irregular intervals, currently numbering around 50. The tension Agatha (1) feels between her lived experience as an artist and the disembodiment and discomfort produced by her work being acquired forms part of this exhibition’s emotional core.

I had previously sent Agatha the available resources on the collection, two books (2) and a link to a PDF listing catalogue details for the nearly 700 works that comprise it. Our task was to put the flesh of an exhibition onto the bones of that information. This week became so densely packed with symbols and stories I remember it now as though it was a dream, everything resonant and meaningful. Each object we looked at became a wormhole.

The exhibition Agatha has produced from this intensive period operates too with a kind of dream logic. In part this is because the parameters of its making create so many loops, shifts and compressions of time and space. Originally initiated by former PICA Senior Curator Eugenio Viola, the project was intended to acknowledge, in PICA’s 30th anniversary year, the significant moment in which these two Western Australian art institutions intersected. In 1995, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of International Women’s Day, Joan Kerr and Jo Holder’s National Women’s Art Exhibition saw galleries around Australia present exhibitions showcasing women’s art. For PICA’s contribution then-director Sarah Miller invited Sir James and Lady Shelia Cruthers, who had been collecting art since roughly the inauguration of International Women’s Day, to exhibit their ‘women’s works’ – then numbering around 120 – at the gallery. The critical attention garnered by this exhibition, In The Company Of Women: 100 Years Of Art From The Cruthers Collection, crystallised the family’s vision for a permanent public home for the collection they had been building, which they subsequently focussed entirely on women’s art. Just over a decade later a Deed of Gift was signed with the University of Western Australia, forming the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art – or CCWA – in its current form.

Artist

Curator