Lillian O'Neil: Soft Demand

It is with great pleasure that The Commercial presents Lillian O’Neil – Soft Demand, the artist’s largest solo exhibition to date and her seventh solo exhibition with the gallery.

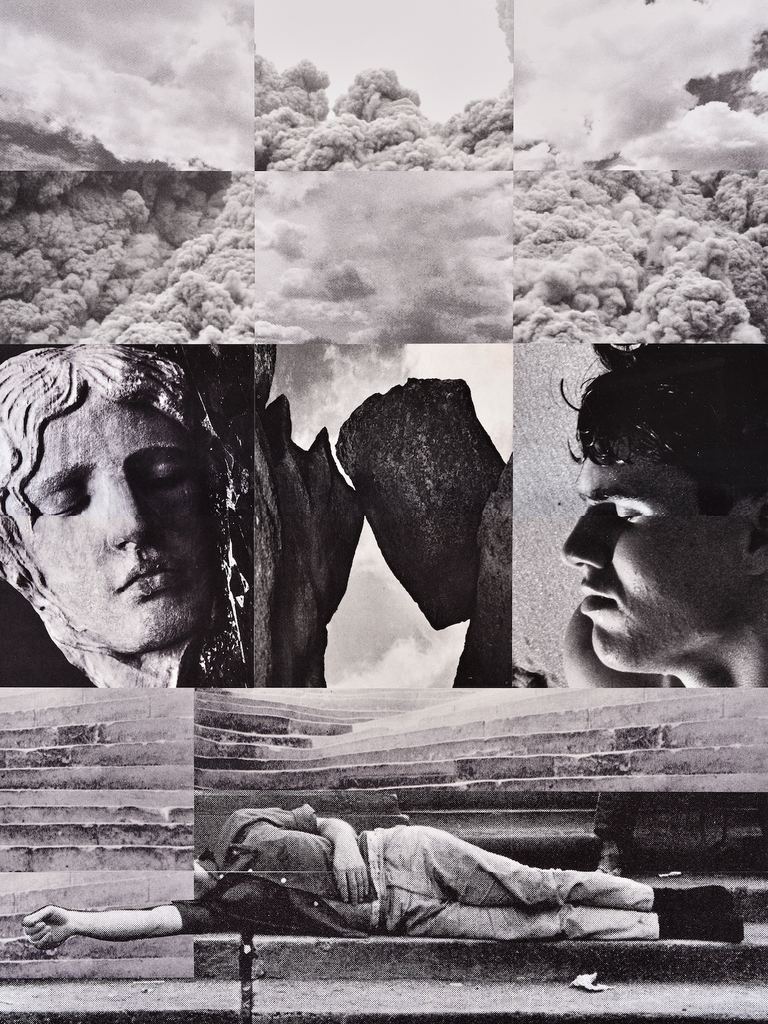

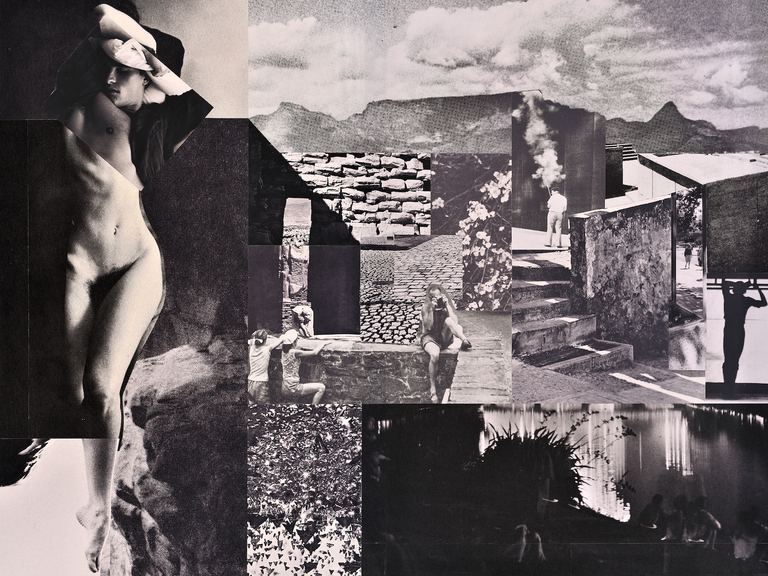

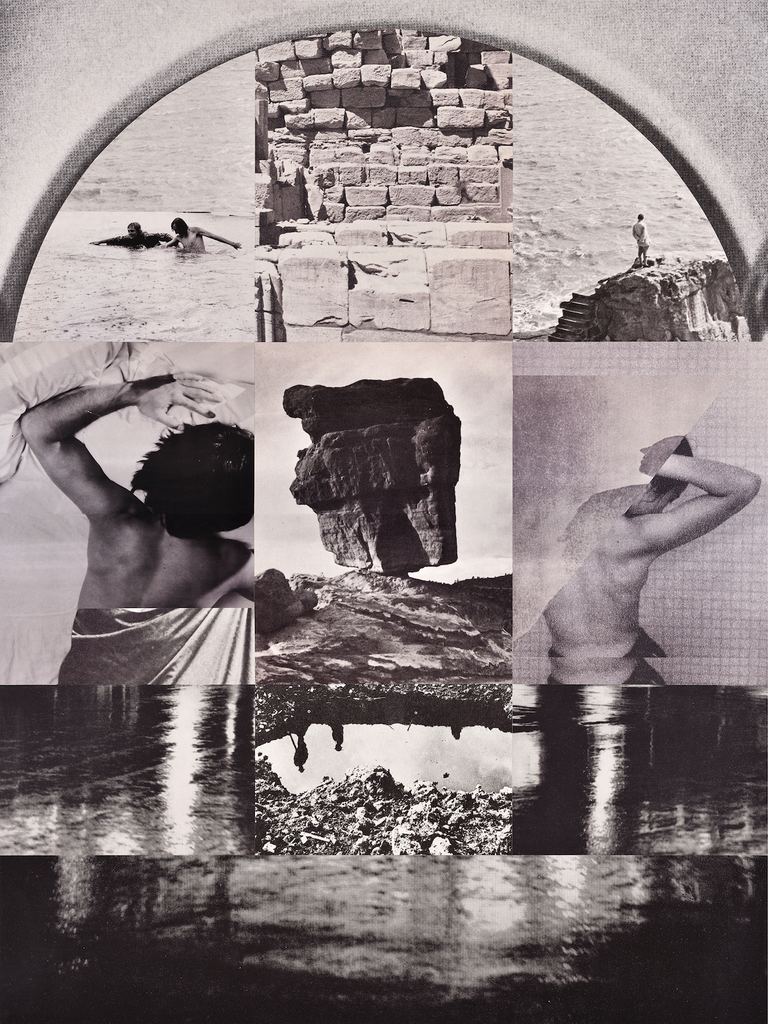

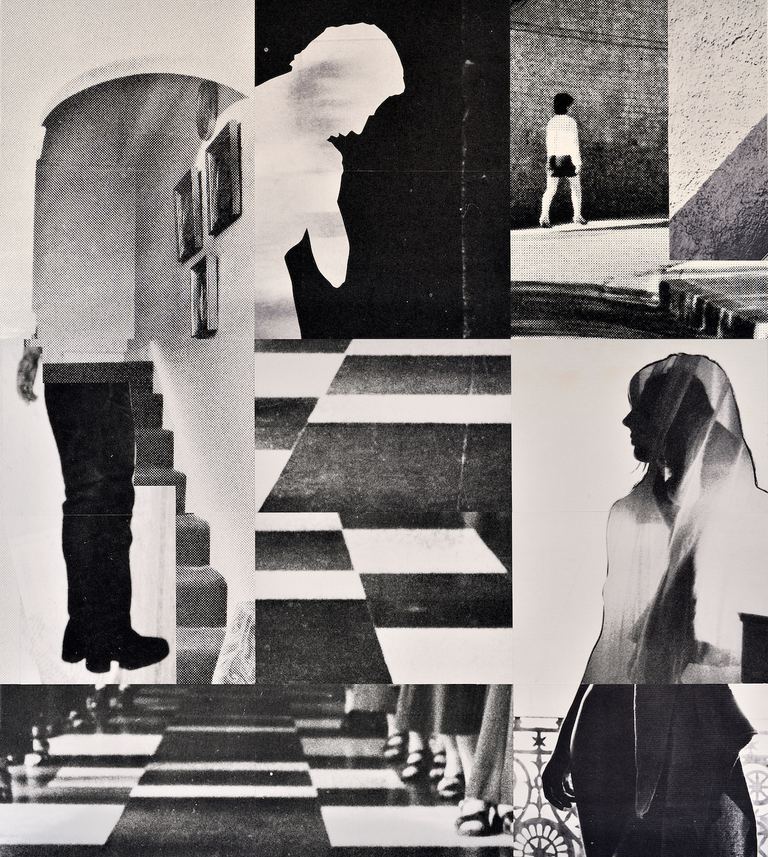

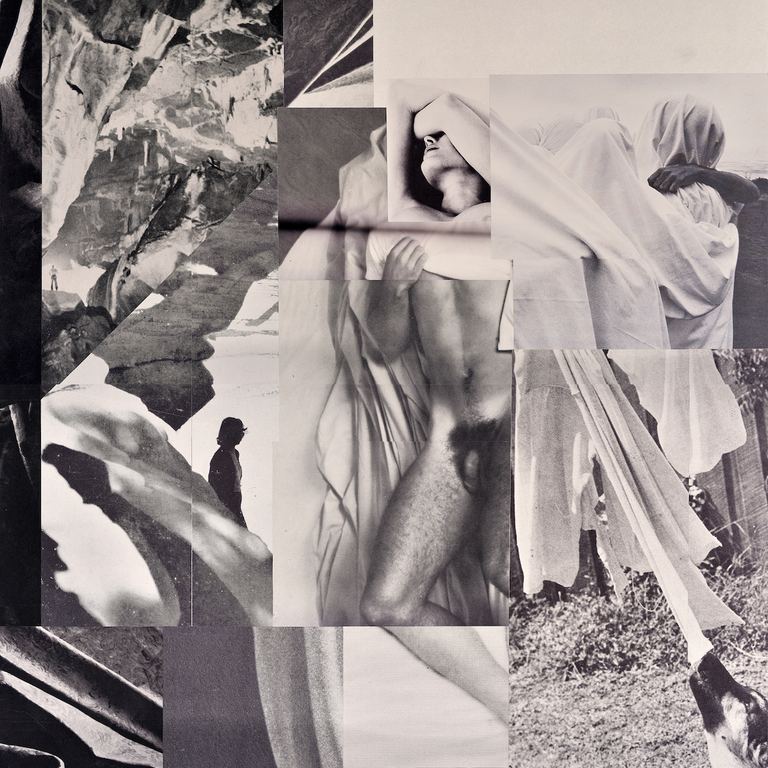

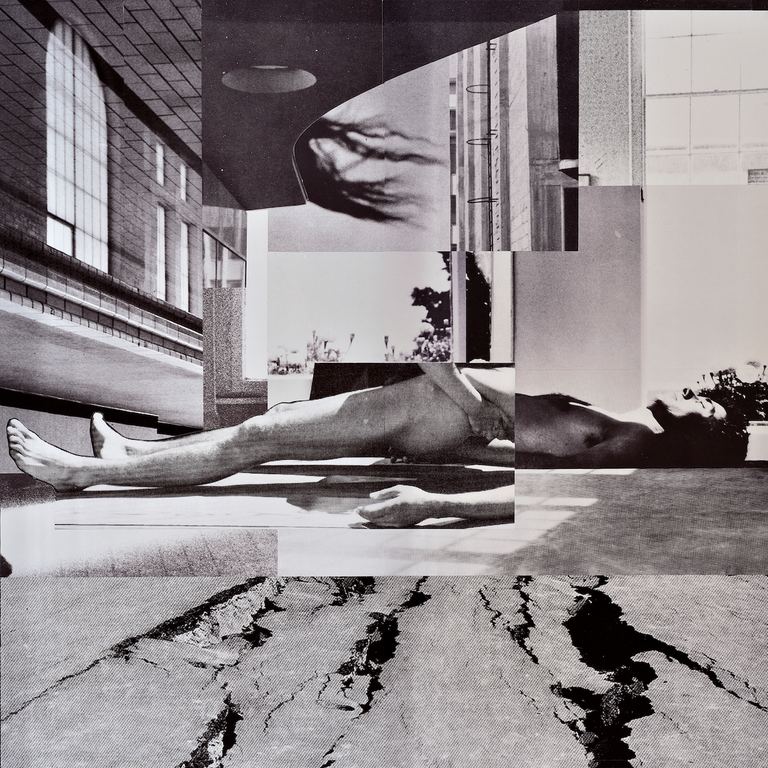

Lillian O’Neil works in large-scale, kaleidoscopic, analogue collage cut from pre-digital books and magazines. The ongoing search for and mass accumulation of material is an important component of her process. Her vast library of material forms a kind of atlas of human activities, interests and beliefs from which she cuts images. In recent years, O’Neil’s collages are composed less from myriad fragments of original found printed material but now employ fewer elements, reproduced and enlarged, venturing into the careful manipulation of scale and jig-sawing of unrelated images into a coherent yet enigmatic whole.

Artist