Inside a pebble, the universe

“I have a feeling there’s something I should see, that something new will break through when the year is up. That hairline cracks have already appeared. I envisage a change in the well-known streets, that in all repetition there is variation...”

Solvej Balle, On the Calculation of Volume: Book 1, (2024)

“Different moments in time hang in space like sheets.”

Olga Tokarczuk, trans. by Jennifer Croft, Flights, (2017)

1.

For the New York-based painter and sculptor Anna Kristensen, the walk from her home in Brooklyn to her studio door in Queens begins in the residential neighbourhood of East Williamsburg. After passing a local park, she makes her way down Metropolitan Avenue—a central artery with four lanes of traffic and a distinct lack of pedestrians—then travels over a canal, past lumber yards and scrap metal lots and a nightclub, all while breathing in the smell, on some days, of a trash collection site, and, on others, of the nearby poultry processing plant. It’s a route that’s marked by the litter of its inhabitants: loose material that blows from one side of the road to the other amidst all the congestion, or collects in the gutter with the onset of heavy rain.

The main thoroughfare that defines Kristensen’s walk, then, is a site with its own specific contours, industries, networks, and peculiarities: no stretch of sidewalk is the same, no square of concrete uniform, and no day without its own weather system, scent, and grab-bag of debris.

2.

Geologists who wish to study the Earth’s structures will often seek out ‘sedimentary depositional environments’—specific locations where sediment accumulates or erodes in response to a site’s unique characteristics. A delta’s sediment, for example, will be shaped by the way a river’s current meets standing water, and a desert’s, by the direction and strength of the winds across its dunes. When Kristensen walks through the seemingly hostile environment of Metropolitan Avenue, with its stench, noise, and rubbish, she finds her own ‘depositional environment’, where each stray item is its own kind of geological deposit and where each slab of concrete harbours its own history. It’s in this setting that Kristensen conducts her fieldwork: recording the pavement’s cracks and idiosyncrasies, gathering detritus, and making rubbings of the littered streets.

3.

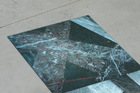

The artist Micah Danges is also working with his own kind of errant material, whether it be an art folio documenting early European Art, or the marble fountain in Philadelphia’s Curtis Centre, originally built in 1910 and renovated in the 1980s. Danges looks at the fountain and sees how it could be transformed into a shadow-play of reflections, curves and light, or he looks inside the folio and finds sheets ready to be dissected and disassembled: the codex resurfacing as flotsam, as relic, as something to be re-mixed. He asks: What new images would we find if we could see through the closed pages of a book? Or, what would we see if we looked at splintered or muddied or multiple images of an object, rather than a single hi-res file?

Yet Danges’ discovery and apprehension of his source material is only the starting point. He breaks apart the folio, for instance, and photocopies page over page over page, layering one image over the other, so as to accumulate a mix of fragmented shapes. (The face of one sculpture might ghost behind another, or a chiselled surface might be intercut with a vaulted ceiling or a black shroud.) Through a process of UV-printing these composite images onto aluminium, he adds yet another layer of chance to the final result—letting the ink run, pool, and dry on the metallic surface. Just as a rockface’s geological strata exposes the sequences and events that have shaped the Earth’s history, so do Danges’ accrued images compress layers of time: there is the sculpture, the photograph of the sculpture taken in the mid-20th century, and its scanned and overlaid reconfiguration in the 21st.

“Some things are not meant to be clear,” says writer and artist Etel Adnan. “Obscurity is their clarity.”1 And Danges’ occluded images, with their splices, echoes, and overlays, relinquish the single point of view in preference for the multiple, for the play between solidity and illusion.

4.

In her use of frottage, Kristensen is also drawing on a method that allows us to look at the discarded object in a newfound way. That is, by making graphite rubbings of the sidewalk’s refuse, Kristensen is creating a transcription of her chosen subject-matter—one that is formed not only by the marks on the paper, but also by the gaps and absences between them. Or, to return to Adnan’s observation: “Obscurity is not a lack of light. It is a different manifestation of light. It has its own illumination.”2 Her rubbings of a used piece of paper towel, for example, disclose what is hidden or overlooked (the imprint of a logo, the trace of a fold), and yet they also transform it into something else entirely (a window, a silvered pattern, a glinting surface now scrubbed clean).

Kristensen’s series of oil paintings, too, which include the door to her studio and the door to her home as book-ends, speak to the joy and wonder that can be found in attending to the overlooked and ignored: the scattered free-fall of a hard-boiled egg casts an elliptical shadow on the sidewalk, a doorknob reflects the morning sunlight, and a copper penny pressed into the asphalt is akin to the shape of a crescent moon. Like Danges’ Xeroxed pages, Kristensen’s paintings amass layers of time and space, and, in doing so, find vastness in the intricate, and the celestial in the mundane.

5.

“We’re all on our surfaces now,” says the novelist Ali Smith. “We’re all on our screens, we’re all looking at things flat, [but] we are not flat, we are stratified creatures.”3 Kristensen and Danges’ work runs counter to this deadening flatness—it’s the opposite of the one-dimensional saturation of the screen, and the antithesis of the digital insistence on speed and virality. What both these artists are offering, then, is a stratified way of looking, one that revels in the tactility of images and objects, in the pleasure of slowness and chance: in layers, depth, sediment, refuse, shards, and fragments; in shadows, hidden glimmers, and the throw-away details of the day-to-day.

Naomi Riddle, 2025

1 Etel Adnan, “Etel Adnan by Lisa Robertson,” BOMB Magazine, (1 April, 2024), https://bombmagazine.org/articles/2014/04/01/etel-adnan/.

2 Adnan, “Etel Adnan by Lisa Robertson.”

3 Ali Smith, in conversation with Sarah Wood, “Gliff in the Spruce Forest”, London Review Bookshop Podcast, (3 December, 2025).