It is with pleasure that The Commercial presents Yasmin Smith — Forest, the first exhibition of the artist’s four-year investigation into coal fly ash glazes sourced from eleven coal-fired power stations around Australia.

“The specific glaze aesthetics derived from a plant’s ash is directly related to the life of the plant, its biology, the soils in which it grew and the underlying geological, hydrological and cultural conditions that makes available certain minerals and elements to sustain its life.” […] “61 of the 118 elements on the periodic table are determining factors in the aesthetics of ceramic glazes.” (Smith)

Where until now, Smith’s wood ash glazes have mostly told stories of plants’ accumulation of nutrients through their lifetimes, Forest is a story about their afterlives, the dissipation and return to the biosphere of those elements over many millions of years. It is also about where humans enter the narrative with their interruption of this eons-deep cyclical process via mining and the exploitation, in various ways, of the carboniferous remains of ancient forests. The magnitude of this exploitation as evidenced by the volume of coal fly ash (Smith's glaze material) created as a bi-product of industrial-scaled coal combustion is such that a new geological sedimentary record has been laid down in our otherwise minuscule human-scaled time. Smith's eleven coal glazes of Forest narrate this timeline over 300 million years.

Since 2018, Smith has exhibited in the 10th Asia Pacific Triennial, the 21st Biennale of Sydney, the 2021 TarraWarra Biennial as well as at Centre Pompidou (Paris), Mao Jihong Arts Foundation (Chengdu), Museo Madre (Naples), Parco Are Vivente (Turin), Monash University Art Museum (Melbourne), Queensland University of Technology Art Museum (Brisbane) and the Powerhouse Museum (Sydney) and her work has been acquired by the Art Gallery of New South Wales (Sydney), the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (Sydney), the National Gallery of Australia (Canberra), the Powerhouse Museum (Sydney) and Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (Brisbane).

In 2023, Mosman Art Gallery, Sydney, is presenting a solo exhibition by Smith, accompanied by a major monographic publication.

Yasmin Smith has exhibited with The Commercial since 2012. Forest is the artist's fourth solo exhibition with the gallery. Yasmin Smith — Forest will be open for viewing during regular gallery visiting hours and by appointment during Sydney Contemporary. The exhibition is accompanied by a text by Kathryn Weir, Artistic Director of the Madre Museum of Contemporary Art Donnaregina in Naples (IT).

exhibition dates: 03.09.22 — 15.10.22

*

Yasmin Smith: Forest

Glossopteris, a giant tree that flourished in Gondwanaland’s swampy forests in the Permian period, makes up much of Australia’s black coal. Unlike the other plants that ended up as coal – horsetails, ferns, cycads and others – it has no living relative and disappeared 250 million years ago at a time when around 90% of earth’s species became extinct following catastrophic volcanic eruptions that released enough carbon dioxide to trigger a greenhouse crisis and drastic global warming. The coal deposits that contain Glossopteris’ ancient forest remains, across what is now Africa, Australia, India and South America, are today at the centre of another climate and toxicity crisis.

In her artistic methodology developed since 2014, Yasmin Smith works with plant ash to make visible what a plant has absorbed in its lifetime through applying ash glazes to ceramic sculptures. She first considered working with coal ash when she encountered ash from the coal-powered steam cranes on Cockatoo Island at the time of the 2018 Sydney Biennial. Ash is a by-product of burning coal for energy, and through further research Smith learned of the huge ‘ash dams’ that have been created next to coal power stations all over Australia, which in turn are built near coal deposits and mines. Australia has around a quarter of the world’s coal reserves, and, according to a recent report on water pollution in NSW, coal ash accounts for a fifth of all of Australia’s domestic waste. 1

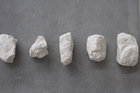

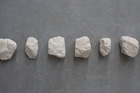

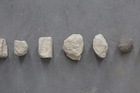

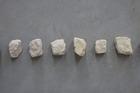

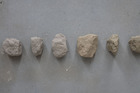

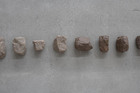

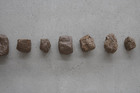

Smith decided to make visible the composition of the ash from as many coal ash dams as she could access. Systematically researching dimensions of environmental science and chemistry, as well as, in the case of this project, of plant palaeontology, her practice also relies on developing networks of collaborators, who may range from scientists to activists to industrial workers. It was only though such relationships that she was finally able to access the ash from 11 power stations from along the Eastern Australian seaboard and in inland areas of New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland. These divide into ashes of black and brown coal, which are coals laid down in different geological periods, from around 300-250 million years ago (black coal), to ‘just’ 66-23 million years ago (brown coal), all constituting concentrated chemical traces of plant and other organic materials formed over time into coal-rich rock through sedimentation, compression and heat. Brown coal, being more recently formed, retains more organic materials and the glazes made from brown coal ash are more highly coloured and textured, showing more plant-like elemental characteristics. Black coal ash glazes on the other hand are almost white, their light colouring reflecting the absence of many soluble minerals deriving from organic materials that have leached away over the longer time frame since the coal was formed.

In the installation, the sculptural elements are arranged in a chronological horizon line that proceeds from the earliest formed ash materials to the most recent. The sculptural forms were moulded by Smith from coal lumps that she selected from a mine south of Sydney, coal in its unprocessed state as it is extracted from its stratum within the geological layers of the earth. The line of the installation evokes the stratum of the underground forest transformed into coal, but also the stratum of ash that began to be visible in the geological record from the 1950s with the exponential increase in coal burning across all geographies in the wake of the coal-fired industrial revolution. It also figures as a horizon line beyond which we cannot see, like the event horizon of a black hole. Temperatures rise as carbon continues to be emitted from coal-burning industries; coal ash dams in the marshy areas around coal deposits continue to leak into ground water. Smith has returned across many bodies of work to industrial and agricultural effluents that flow into water systems, toxic presences to which her plant ashes testify. Her most recent major body of work produced in 2021 near Naples in southern Italy explored the disaster of illegal industrial waste disposal buried in agricultural fields dubbed the ‘Terra dei Fuochi’. While coal in the ground is not toxic, the concentration of certain heavy metals in the ash produced by burning coal makes this coal burning by-product highly toxic. There is potential for greater re-use of the ash in asphalt, bricks and cement, but if more is not done to remove and repurpose this material, many tonnes of heavy metals will continue to leach into the waterways from unlined coal ash dams in coming years.

Smith speaks of her motivation in creating this work:

‘I’m attempting to represent a cycle of growth> death> coalification> extraction> reduction> return. From the Industrial Revolution onward, sections of humanity have dug vast amounts of coal from the earth leaving voids where forests once stood. A seam of geological time is removed. We then burn the ancient forest and resow its ashes back into geological time, returning the ashes to the earth’s surface and creating a new stratum. The accelerating industrialisation globally since the 1950s is a likely candidate to mark the entry of humanity into the geological time-scale, defining the so-called Anthropocene. When considering the massive, industrialised extraction and use of coal undertaken by humans since the mid-19th century, as a contributing factor to changes in earth’s systems and climate, I think about the morphological changes that this activity leaves behind; the physical void 300 million years down, where coal was removed from geological time and the drastic changes to contemporary terrain to reach those depths. But to officially enter the Anthropocene into the geological record, evidence of humanity must be defined in geochemical strata as it is laid down on the earth and contributes to a new geological age. If you ask what humans contribute to the geological fabric of the earth, the answer is fly ash from coal combustion. The spectrum of coal ash glazes in Forest present a visual understanding of this geochemical contribution.’

KATHRYN WEIR

ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, Madre Museum of Contemporary Art Donnaregina, Naples, ITALY