Specters of Globalization

text by Matthew Taft

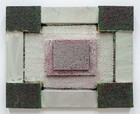

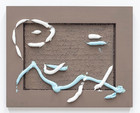

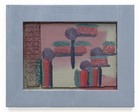

Zone, Dreadnaught, Pontoon. The early twentieth century haunts Oscar Perry’s new body of work, ‘Spoorloos’, a collection of small-scale sculptural paintings. The works conjure landscapes pockmarked by the ravages of war, a generation shell-shocked and broken, flags shredded and bloodied. The twilight of the European nation state as its global power fractured. As for politics, so too for painting. Abstract space, geometric forms, non-objective composition. The formal contours that furnished modernism’s artistic hegemony. But again, only as something pallid, insufficient, and fading. The excessive spatter of Sanitorium rupturing the frame, the viscous flatlining of EKG putting paid to any purity of line, and the recurrent sponge-induced depths resisting the flatness of abstraction. The title of the show refers to a 1998 Dutch film translated into English as The Vanishing, which begs the question, what has vanished? This, it seems to me, is that which Lenin once identified as the second stage of capitalism, the stage of monopoly and imperialism, and along with it, let me add, the modernism that was its artistic form.

As one form vanishes, another takes its place and, so, into this breach steps a new mode of political control and corresponding aesthetic form. Let me wager that the real focus of Perry’s paintings is not the decline of the early twentieth-century nation state and the withering of modernism but rather the succeeding period and its attendant representational challenges. To suggest as much implies there is a missing term, one constituting the substructure and providing the imperative, force, and propulsion behind Perry’s updating of geometric abstraction. That word is globalization, the third stage of capitalism signaling capital’s unparalleled expansion as its reach covered the globe. That this term appears absent or, as we will see, is only apparent in the sinews of the form, should come as no surprise. For this new power is not that of nations and visible architecture but that of economic conglomerates and invisible infrastructure. We must not fall prey to a reductive equation between representation and the real, in which globalization is only present when it is directly represented. For how do we represent a system that is empirically real and yet absent to any individual perception of that totality, where the visible signs are only ever impressions of an underlying mode of production that cannot be captured by surface images? The capacity to map the global system, that is, is a representational problem. An aesthetic capable of unveiling this reality has less to do with charting the flows of finance, information, and people, and more to do with the problems of figuration.

Let us return to where we began. A haunting. But now, seen from the proper perspective, this is of globalization. As for politics, so too for painting. Can we not see this aesthetic articulated in the materiality and facture of Perry’s work? The sponges, so suggestive of globalization’s dematerialized reality, absorb and structure the loose brushstroke much as the market clogs and channels financial flows. The frames’ incapacity to organize space as the formal counterpart to globalization’s diffusion of political power. The yearning, as in Autopsy and X. RAY, to capture the underlying reality that determines experience. Alongside these formal gestures, serving as an expression of our inability to situate ourselves within globalization’s political order, can we not also discern a latent utopian impulse? Every haunting, after all, possesses its own specters. This impulse is not located in any singular work but in the very multiplicity of the works themselves, some fifty-odd paintings. A multiplicity auguring some future collectivity, an as-yet-unknown force perhaps capable of challenging globalization’s grasp. Time, as it tends to do, will tell.

Matthew Taft is a writer based in Melbourne and a PhD candidate at Duke University.